Ever since I entered higher education as a student quite a few years ago, graduating in four years was the most significant stressor for college students. I struggled to live up the pressure of graduating in four years. I found myself taking on way too many classes to graduate in four years and found myself on academic probation until my Junior year. I forced myself to stick with a major I hated too long out of fear of not graduating in four years. It wasn’t until my mentor asked why I was so hell-bent on graduating in four years? I merely replied, “because I was told to graduate in four years.” That’s when I found out most college students don’t graduate in four years and that is still true to this day. The National Center for Education Statistics (2015) found that only 39% of college students graduated in four years. That number increased when looking at five-year graduation rates to 55% and 59% in six years. Graduating in four years is a myth. It is not a real thing, but education keeps chasing it and failing students in the process. Many institutions have excessive degree requirements which require students to complete more than 120 credits for a bachelor’s degree (Complete College, 2014). Yet, we are still judging students on a fake four-year marker.

So why are the government, states, and higher education institutions so aggressive to increase the four-year graduation rate? You already know the answer, it’s all about money. Money in higher education is two-fold. The more students we can graduate faster, the more people we can give jobs to spend money to dump into the economy. The more students an institution can graduate the more students they can flood on overcrowded classes. I can’t blame the institutions for looking to increase revenue because budgets are getting slashed left and right. Yet, these same institutions with gutted funding are expected to increase four-year graduation rates while simultaneously cutting academic support programs.

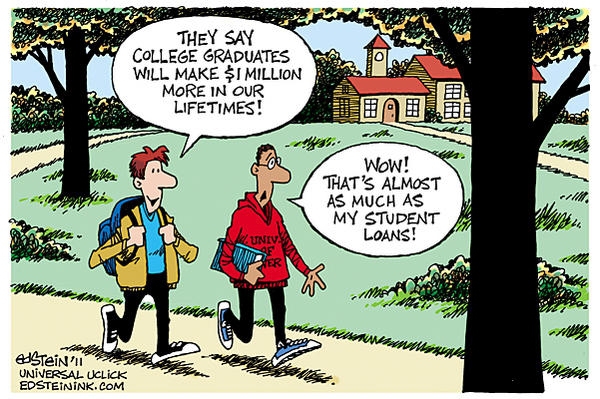

The cost of higher education is steadily growing, and more students are finding it more and more difficult to fund their education. The average cost of a public college education rose by 30% from 1995 to 2005, and 21% over the same time period at private colleges (Raikes, Berling & Davis, 2012). Because of this students are taking on more credits a semester/quarter to graduate as fast as possible to save money. Yes, I know research shows that students likelihood of graduating increases if they take 30 credits in their first year (Complete College, 2014). I am all for saving students money but if we are forcing them to take on courseloads that they are ill-prepared to succeed in, are we, in fact, costing them money? You know what’s more expensive than obtaining a college degree? Not finishing a degree.

Courseloads is just one of the problems with chasing four-year graduation rates. Students are flaming out in college because we have forced students to take far too many credits in majors they hate and unprepared for. Wouldn’t the possibility of graduating also increase if we allowed students to take one less class and didn’t scare them into trying to graduate in four years? My five years in college was filled with self-exploration and growth. The frenzied rush to graduate students in four years has eliminated students opportunities for growth and self-exploration. As a first gen low-income student with a crazy amount of student loans I understand the fifth year in school is not the best option in the world due to its price tag. Also as a first gen low-income student graduating in five years gave me the opportunity find the major that was right for me, gain valuable experience outside of the classroom that has benefitted more than any class I ever took and it allowed me to build a network that has served me quite well in my profession.

I have no clue how to fix the problem of students not finishing their degree. What I do know we are failing students chasing a target that is unattainable for so many students. It’s unattainable for many reasons and not its just lack of preparedness. Remediation has been one target of four-year graduation initiatives. Many students take for credit remediation classes that aren’t applied to their degree which increases the amount of time to graduation (Rippner, 2016). What about life events that force students to deal with life. In my sophomore year, I lost a close relative three straight weeks towards the end of the Fall semester. Life dealt me a massive blow that impacted my progress not only as a college student but in life. Four-year graduation rates don’t account for life, and yet we continue to point at it as a marker for effectiveness.

I started this blog post with the intentions of putting together a cohesive argument about the four-year graduation myth. I am 870 words in, and I have lost my way. This might be a microcosm of the four-year graduation rate chase. In my honest opinion, I feel higher education has lost its way. To improve education and economic efficiency the experiences and journey of college students have been forgotten. From guided pathways to selecting a major upon college admission, there is no room for exploration because institutions, states, and the government have deemed churning out degrees is more important.

Complete College, A. (2014). Four-Year Myth: Make College More Affordable. Restore the Promise of Graduating on Time.

Raikes, M., Berling, V., & Davis, J. (2012). To Dream the Impossible Dream: College Graduation in Four Years. Christian Higher Education, 11(5), 310-319.

Rippner, J. A. (2016). The American policy landscape. New York: Routledge.

Jefferey,

Bravo for having the courage to put this out there and to use your own experience as an example. I fully agree with you that higher education has lost its way in trying to force four-year graduation rates on all students, regardless of major, level of academic preparedness, and, as you mention, total disregard for life-changing events. Why are we pushing our students to graduate in four years if they leave college no better educated and/or prepared to take on a career than when they entered? Or forcing them to choose a major as freshmen, only to find out two or three years into it that they have no real interest or motivation to graduate with said major?

I agree that there are a combination of factors leading to this aggressive push for four-year graduation rates, with money being the biggest concern and motivator. But this push comes at what cost to society? Perhaps education policymakers should return to the broader mission and purpose of postsecondary education. Is it simply to grind out graduates who can enter the workforce in four years? Is it, as you described, to provide students opportunities for self-growth and discovery? Or is it somewhere in between?

I sense that the purpose of postsecondary education may be all of those things, but the problem is that our current system of public postsecondary education is that our institutions are trying to answer to every student’s needs when there is no one-size-fits-all solution. We may need to radically rethink the way that our educational institutions work — and the ways they are funded — to meet the complex needs of a diverse population. The question is whether this is possible given the entrenched interests in our current system.

-gena

LikeLike

I really struggle with the emphasis on the 4 year graduation rate as well for all of the reasons you shared here. In addition, I think that a university needs to take into account the nature and demographics of your student population. The four year graduation rate does not acknowledge the reality of Cal State LA students — the majority of whom are first gens and who have many, many responsibilities outside of the classroom. OUr students are taking care of their families and working two or three menial jobs on top of a full course load. We have to acknowledge the reality of our students if we truly want them to be successful.

LikeLike

Hi Jeffery,

I never understood why the CSU system was so afraid of double majors / students going over their 120 unit limit. I think college should be a space for exploration and growth, as you said. There was even a point where they were forcing students to graduate with a generic “collegiate studies” major if they had gone over a certain number of units, or even talk of cutting off financial assistance.

Unrelated, but remediation is a big conversation in college. If we subscribe to the notion that college is for everyone, is there a place for students to take courses below college level? At my campus, there is talk of making “bridge” type non-credit programs for students to catch up to college level. They would be no/low cost for students, but the students wouldn’t technically be students until they’re at the college level. I understand this as a response to AB705, but I also know that many of my students are taking my college-level course at the same time as a remedial other-course (English or math), and they are doing fine. Some students are even just afraid to take some topics (cough math cough) and put it off forever.

I can’t relate to your frustration about your major, but my sister could. She was nearly graduating before she decided to make her major change official – but by then, they had changed the requirements. She was so frustrated, she just graduated with what she had.

Tracy

LikeLike